- Image via Wikipedia

The Name of the Church

The Coptic Orthodox Church is also known as the Church of Alexandria, Alexandria being the capital of Egypt during the Greco-Roman period. The word “Copt” derives from “gypt” in Aigypptos, the Greek word for Egyptian.

Historical Origins

The Copts pride themselves in the apostolic origin of their church, which was founded by St. Mark the Evangelist. He is regarded as the first of the 117 Patriarchs of Alexandria, as well as the first of many Egyptian saints and glorious martyrs. St. Mark is believed to have come to

Alexandria between the years 48 and 55. His first convert was names Anianus, whom he later ordained bishop to be his successor, together with three priests and seven deacons. St. Jerome states that St. Mark established the School of Alexandria, which became the highest center of theological education in the Middle East. He was martyred in the year 68 and buried under the altar of an Alexandrian church. In 828, Venetian merchants took the headless body of St. Mark to Venice while the head remained under the altar in Alexandria. In 1968, thanks to the good relations between Coptic Pope Kyrillos VI and Pope Paul VI, a part of his relics was returned from Venice and buried under the altar of the new Coptic Cathedral in Cairo.

Turning Points in History

The Coptic Church was subjected to various persecutions under the Romans from 69 to 639.

So profound was the impression of the persecution of Diocletian on Coptic life that the Copts date their Calendar of the Martyrs from this epoch. The first year of this calendar, A.M. 1 (Anno Martyri), is 284, the disastrous year of the accession of Diocletian.

In 312, Constantine the Great’s edict of toleration ushered in the triumph of Christianity over paganism and the reversal of the policy of persecution. Old pagan temples were transformed into Christian churches. Christianity became the state religion in 381.

Despite this long period of Roman persecution, Alexandrian Christianity was renowned for its saints, the Fathers of the Coptic Church, and the great theologians of the School of

- Image via Wikipedia

Alexandria (Pantaenus, Clement of Alexandria, Origen).

The great name to emerge as the head of the school was Pantaenus (d. 190). He was succeeded by Clement, who was followed in about 215 by his brilliant student Origen, one of the greatest exegetical sc

holars of all time. After his discord with Patriarch Demetrius, the school came under the direct control of the patriarchal and church authority. Origen’s immediate successor was Heracles, his former pupil and assistant, who later succeeded Patriarch Demetrius on the See of St. Mark from 230 to 246. It is said that when he increased the number of local bishops to twenty, the presbyters of the church decided to distinguish him from the rest of the bishops by calling him “Pope,” a common title for bishops of Alexandria from the third to the fifth centuries. Among the most reputed scholars who headed the school was Dionysius of Alexandria, later surnamed “the Great” (Patriarch from 246 to 264). His successor was Didymus the Blind (265 to 298). The school played a crucial role in shaping Christian doctrine and theological scholarship during the first four centuries.

The attempt to eradicate heresy and doctrinal differences among the various centers of Christianity bore fruit in the first three Ecumenical Councils of Nicea (325), Constantinople (381) and Ephesus (431). Two spiritual and intellectual leaders of the Coptic Church, St. Athanasius and St. Cyril of Alexandria, played predominant roles at these councils.

Beginning in the fourth century, Pentapolis, Nubia and Ethiopia were recognized as being under the jurisdiction of the See of St. Mark.

Coptic monasticism was a gift of Egypt to Christendom. From its modest beginnings on the edge of the desert, it developed into a way of life that was a wonder to Christian antiquity. Most writers ascribe the origins of monasticism to St. Anthony (c. 295-373), whose fame was spread by St. Athanasius’ Life of Saint Anthony. Pachomius (d. 346) introduced the cenobitic system in 290.

Following their rejection of the Council of Chalcedon, the Copts suffered fierce persecution at the hands of the Chalcedonians.

After the Arab conquest of Egypt in 640, the Copts continued their unwavering loyalty to their church and to the faith of their forefathers.

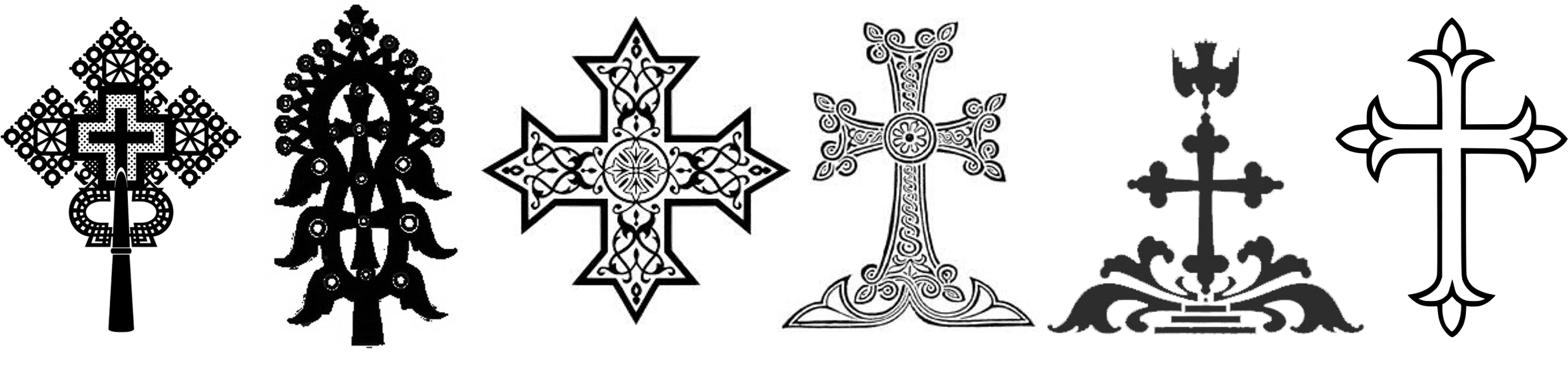

The Copts had to give up many material privileges in order to retain their spiritual heritage. Before the Crusades, however, they adapted themselves to the conditions of Islamic rule without the loss of their way of life, and were generally accepted and often esteemed by the caliphs. They were the clerks, tax collectors, and treasurers of the caliphate, and they seemed able to make themselves indispensable to the civil service. The Crusades antagonized the Moslems toward all “worshipers of the Cross,” whether Latin, Greek, or Coptic, and the difficulties of the Copts remained acute under both the Mamluk and Ottoman regimes (twelfth to eighteenth centuries).

- Image via Wikipedia

During the French occupation of Egypt (1798-1801) and the reign of Muhammad Ali (1805-1850), the situation improved. Copts were widely used in the administration and some rose to high office.

In 1959, under the late Pope Kyrillos VI, there began a renaissance of all aspects of church life that is still very much in progress under the present Patriarch, H.H. Pope Tawadros II.

The Coptic Church is a member of the World Council of Churches, the United States National Council of Churches, and the All-Africa Council of Churches.